Zoë Ghyselinck’s World of Reading

Schopenhauer famously said that reading is thinking with someone else’s head. But what is it that we hope to find in the other person’s head? Peace and quiet, distraction, knowledge? Welcome to the World of Reading, a series of interviews in which we talk about the role of reading, beauty, and language. In this instalment literary scholar we meet with Zoë Ghyselink.

Interview by Matthias M.R. Declercq

Translated by Sandy Logan

-> naar de Nederlandstalige versie van dit artikel

‘My world of reading is almost entirely grafted on what is known as fiction’, Zoë says. ‘I very rarely read non-fiction. Not that I refuse to, but I prefer a fictional world, even when it draws on historic events and facts. To be honest, I think that the separation between fiction and non-fiction is somewhat obsolete anyway. I enjoy Stefan Hertmans’s auto-documentary-fiction just as much, for example.’

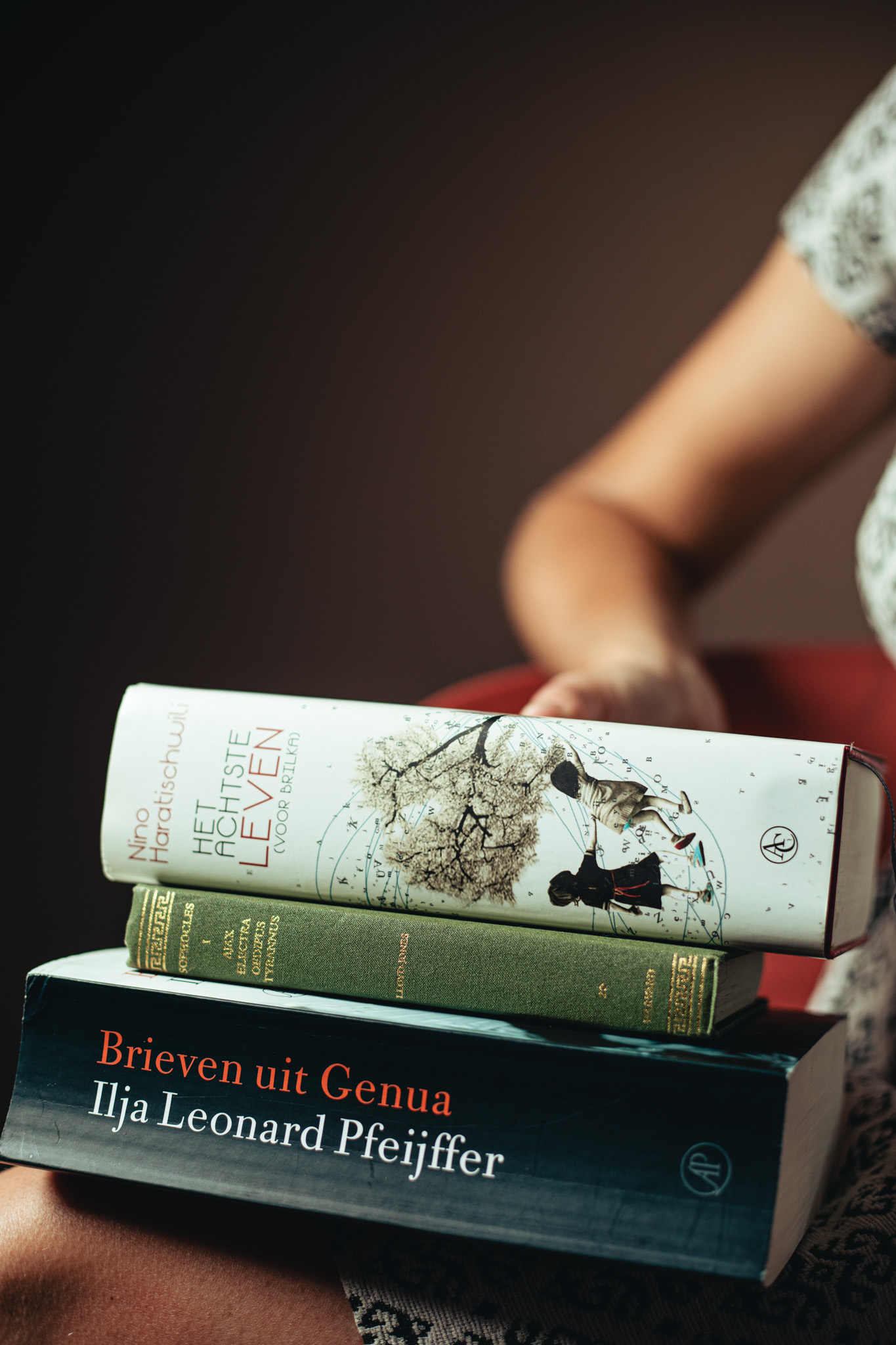

Zoë Ghyselinck doesn’t need prompting with questions. She easily establishes links between all the points and explains very clearly what reading means to her. Fiction is the backdoor through which she escapes reality only to re-immerse herself into it afterwards, although she only realised this much later in life. Some time ago, reality imposed itself on her, raising questions about the fiction. ‘After the birth of my first child, I read Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer’s books. Wonderful literature in which reality continually blends in with fiction and in which the tension between them is a theme.’

‘Stylistically speaking, Pfeijffer’s work is a powerhouse, especially Letters from Genoa, in which he uses various perspectives in genres. The narrator writes a letter to his younger self, midway in the novel. A rather obvious reference to Dante, but also a highly commendable attempt to position his epistolary novel in the tradition of the ‘grand narratives’. “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” (midway upon the journey of our life) is the first verse of Dante’s Inferno in La Divina Commedia. When you experience a setback midway in life, whether psychological or spiritual, you can go through hell and come out stronger on the other side.’

‘Not that I was suffering from depression as a young mother, while reading Pfeijffer. But I felt that I had come to a standstill, a point of retrospection and introspection. While reading Letters from Genoa, I faced an existential question: I am always engrossed in fiction, including in my work, but now the reality is here, next to me, in the form of a baby on my arm, and it is more important than fiction. What crossroads have I come to, as a person, as a mother? Where am I heading? Should I continue down the same path? Fiction was not relegated to the background. Instead fiction, and its multiple perspectives, taught me to see reality through different eyes, to appreciate it even.’

Fossil

Essentially Zoë Ghyselinck is a literary architect. When she reads a book, she immediately discerns the floor plan of the story, she can trace the load-bearing beams, knows where and when the light falls in and which unfinished corners the writer likes to conceal from view. Ghyselinck studied Latin and Greek, after which she obtained a PhD in literature on the impact of Greek tragedies on modern German literature. She works as a postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University, in addition to being a guest lecturer on General Literary Science at the Catholic University of Leuven. She also studies the relationship between the speaking dead and new communication tools in modern and post-modern literary imagination.

‘At family get-togethers I could always be found in a corner reading a story. I was the child that would crawl under the table in a restaurant with a book’, says Zoë. ‘I was always the strange one, with her books. At my own birthday parties I would read, while my mum played with the other children. (laughs) ‘We didn’t really have a reading culture in Ghent, in Meulestede. Although my aunt and my mum were frequent readers and we had a copy of Eugène Sue’s Mysteries of the People on our book shelves, which was more or less hidden from sight. For many years, this series of socialist books (about a family of labourers) was banned. Perhaps my mum succeeded in covertly obtaining it from her parents or grandparents. My mum and dad didn’t have to read stories to me for too long because I taught myself to read at the age of five.’

‘As a child, I was really into history. I had a small cabinet full of archaeological finds in my room, such as fake papyrus scrolls and an old coin that my dad – who did odd jobs in various Ghent museums – had found one day. This penchant for the past also manifested itself in my world of reading. I would read an eight-part series about the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses or about Nefertiti. I also tremendously enjoyed all of Thea Beckman’s books, and Crusade in Jeans in particular. Reading gave me an outlet. I didn’t like to dress up as a princess, but I would sit in the sofa and let my mind roam to other worlds, like ancient Egypt. Not that I had to flee the reality of my own family, not at all. But in those days, I already thought ‘is this it?’ about the world. And apparently yes, this is all there is. Fortunately books gave me a different perspective, which I found infinitely more challenging than the world around me.’

Lasciate ogni speranza

A world of reading that develops from a young age stands to benefit from some guidance. You can get this from your father, your mother, your siblings, your neighbour, but also from the local librarian. Zoë Ghyselinck’s world of reading was partly shaped at school. ‘My Greek teacher wrote “Lasciate ogni speranza voi ch’entrate” (Italian for Abandon hope all ye who enter here) on the blackboard. In doing so, she taught us some Italian in addition to kindling our historical awareness. It was amazing. Dante’s cantos fuelled my imagination. And although Dante is not an author of classical antiquity, his work led me to read the ancient Greeks, such as Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey. I reread them in Greek now and then and I also read children’s versions of these books to my son and daughter. My son’s name is Hektor and he keeps his little sister entertained with stories about Cronos and Perseus’ (laughs).’

“I read children’s versions of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey to my son and daughter. My son’s name is Hektor and he keeps his little sister entertained with stories about Cronos and Perseus.”

‘The more you read, the more books cross your path, and the more you realise that there is so much to read. I still feel as if I really didn’t read all that much. As a teen, I read all the great Russians, such as Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. I noticed that my mum would read a book now and then by the Chilean author Isabel Allende, which led me to Gabriel García Márquez and all those other Latin American writers. (North) Americans such as Don DeLillo and Paul Auster still await. At university, I discovered new names such as Cervantes and his Don Quixote, Gustave Flaubert and Thomas Mann. Although lecturers now fortunately pay more attention to a more inclusive and dynamic overview of literature, I don’t feel the need to delve deeper into it. The literary ‘canon’ is enough for now.’

The Eighth Life

‘Why I read and what I read hasn’t changed that much since childhood. I still love fiction and I still love history in fiction, preferably the psychological kind. The impact that Crusade in Jeans had on me as a child is similar to what I felt as an adult when I read Nino Haratischwili’s The Eighth Life. So visual, so dramatic, so much better than a film. I find this book fascinating, both because of the theme and the style. The fictional story of eight generations of the same family is told through the perspective of Georgian history and mainly unfolds against the backdrop of the very fascinating 20th century. Whereas others like to unwind over a drink after a day’s work – which I also do now and then -, I like to retreat to the comfort of my own home, with a book. Only to quietly return to reality, to my children, after reading.’

‘I need fiction, outside of work. In my graduate year, my professor of Greek literature asked me whether I would ever be able to enjoy a book again, after my studies? Or whether I would be continually tempted to analyse its structure, the narrative voice and so on? Of course, I can. That said, I’m not overly bothered by analysis, which comes almost automatically to me. I can immerse myself in a book at any time. Fiction and reality don’t exclude one another. They are complementary. Reading is fundamental to my life, like breathing.’

Worlds of reading

Discover more inspirational interviews with readers.